First Jewish immigrants settled in Tarnów region in the Middle Ages. Their presence in the city is mentioned in 1445 writings. From the very beginning their commercial activities focused on wine and grain trading which they imported from Hungary and Russia.

Jewish entrepreneurship was appreciated by the Tarnów owners. In 1581 Konstanty Ostrogski issued special rights allowing Jews to trade in their houses, kiosks and market square. They were also granted right to brew and trade alcohol beverages.

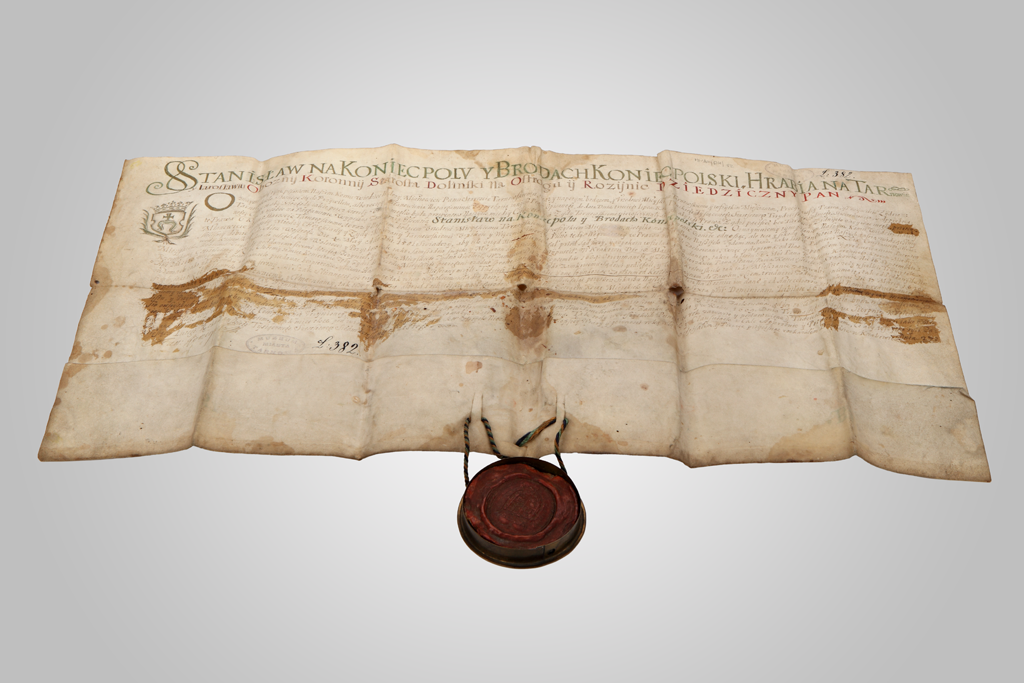

Picture: Manuscript “The privilege of Stanisław Koniecpolski for Jews from Tarnów” with a seal

source: http://muzea.malopolska.pl

On the behalf of those rights Jews were incorporated into castle’s jurisdiction therefore no longer came under the laws of the city of Tarnów. New law allowed tough punishment for any acts of vandalism against Jewish prayer houses or a cemetery. Jews were also allowed to settle 12 houses along Żydowska (Jewish) street. Substantial changes in law attracted numerous Jewish families to move to Tarnów region. The limitations regarding settlement of Jews within the city of Tarnów were lifted in early 18th century by duke Sanguszko.

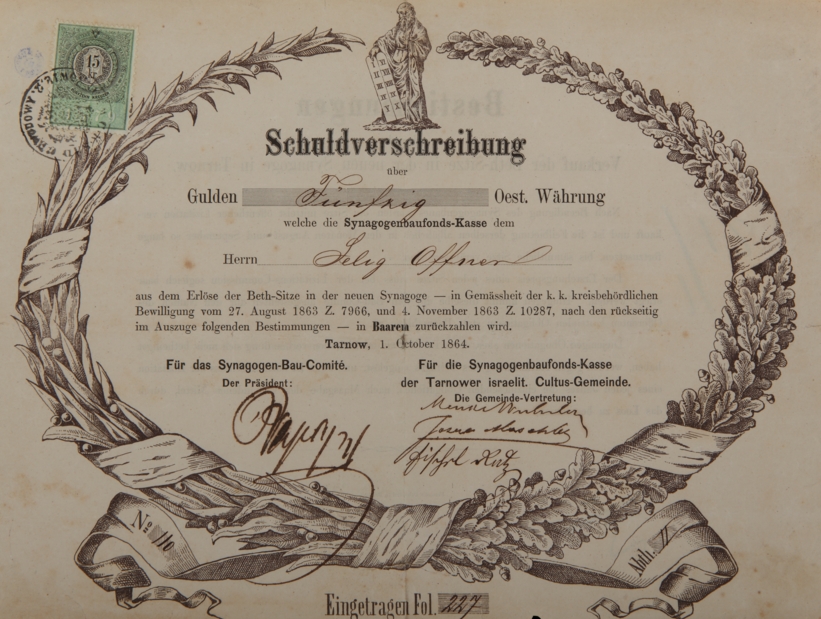

Some of the Tarnów Jews belonged to the intellectual and cultural elite. Their professions were those of public trust and respect like attorneys, doctors, musicians or teachers. In the 18th century Synagogue in Tarnów covered nearly half of the city tax income, apart from the taxes paid by individuals. Tarnów region with several dozens synagogues and small prayer houses was an important religious center. There were Jewish schools and printing houses operating in the city. Social and cultural life were blooming.

Picture: Bond Committee for the Construction of the New Synagogue in Tarnow

source: http://muzea.malopolska.pl

Today however there is no Jewish society anywhere in Tarnów region. No public worship that requires minyan (10 adult men over 13) could be completed. But there are numerous traces left which document centuries-long Jewish presence in Tarnów region. Cemeteries are the most numerous monuments of Jewish history. Some are very well preserved and cared for, other forgotten and demolished. The original Jewish architecture, bath houses, schools, archives and synagogues can be found throughout Tarnów region. Most of the buildings are still in use today but serve different purposes than originally. Numerous places commemorate Jewish oppression and Holocaust. Rich judaica collections are stored in few museums. Those of greatest value are exhibitions in Tarnów Regional Museum and museums in Dąbrowa Tarnowska and Bochnia.

Żydowska and Wekslarska streets outline former Jewish quarter of the city. The 17th and 18th centuries buildings preserved there represent the most common type of dense architecture with narrow passages between the houses and tiny backyards. Unique for the east part of the Old Town are narrow facades. In the door frames of some of he houses the traces of mezuzahs (piece of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah) can still be found. In several houses iron window shutters of former Jewish shops and stores are still in place.

Through the gate on Żydowska (Jewish) street one can enter the square, where up until the WWII stood the 17th century Tarnów Synagogue, the oldest of city’s prayer houses. It was burnt down by the Germans. Only the Bimah (elevated area from which the Torah is read) survived. In 1996 the Committee for Renovation of Jewish Monuments in Tarnów launched the first edition of Galician Jews Remembrance Days. Since then, music concerts and various performances are held in the square each year. A plaque on the corner house of the Żydowska and Piekarska streets commemorates liquidation of Tarnów Ghetto. During the WWII, the Old Town witnessed mass-murder and martyrdom of local Jewish population. Tarnów Regional Museum’s collections hold diverse pieces of judaica including the original (1667) document granting new rights and privileges to the Jews of Tarnów; three Torahs and records from the last prayer house in Tarnów.

Dr Eliasz Goldhammer’s (vice-mayor) contribution to the development of Tarnów was awarded by giving his name to one of the most important Jewish streets in the city. Such a privilege, given to the Jewish citizen, was a precedent decision in Poland at that time. On both sides of the street there are houses once belonging to the elite of Tarnów Jews.

In a house number 1, there used to be a prayer house, closed in 1993. The most prestigious of Tarnów hotels, Herman Soldinger’s hotel, was located in a house number 3.

The house number 5 was occupied by Tarnów Credit Union, whose general director was Herman Merz. In a hall of the building two plaques remind great citizens – Eliasz Goldhammer and Herman Merz. On the opposite side of the street – on the facade of a house number 6 – one can see a menu of a restaurant once operating here. Those menus are in two languages: Yiddish and Polish.

Steam semolina mill established by Henryk Szancer in 1859 had an immense influence on modernization of mill trade in Galicia through increasing its efficiency considerably in a short time. Acting as a trading partnership Szancer and Freund launched another steam mill in Tarnów in 1865. In the 80’s of the 19th century mill paid taxes eight times as high as other mills of Prussian Upper Silesia did. This fact indicates the immensity of enterprise of Tarnów’s traders.

Ritual bathhouse – Mikvah was erected in 1904 in Mauritanian style. It became infamous assembly point of the prisoners deported to KL Auschwitz in the first transport for newly established concentration camp.

Jewish cemetery, founded in 1581, is one of the oldest and most interesting cemeteries in southern Poland. Over four thousand graves can be found there. It was devastated by the Nazis during WWII, and turned into the place of mass slaughter of Jews from Tarnów’s Ghetto committed from June 1942 to September 1943. After the war, in 1946, Dawid Becker, a Jewish sculptor, placed on a mass grave a monument – broken column coming from the ruins of the New Synagogue in Tarnów. Engraved inscription in Hebrew says: “And the sun shone and was not ashamed…”.

The places of Tarnów region used to be important centers of Jewish culture. Small towns lacking in large-scale industry were one of the centers of Hassidism in Poland. Jewish councils from Małopolska area gathered in Dąbrowa Tarnowska and thus it is the place many eminent tzadiks came from. Dawid Unger, the founder of the famous Unger dynasty, as well as Cwi Hirszem Rymanower, later tzadik of Rymanów, came from Dąbrowa Tarnowska, one of the most significant centers of Hassidism. Today, Jewish heritage of the town is scarce, yet impressive. Recently renovated building of a synagogue (with ornamented facade, arched windows and richly decorated interiors) is considered the most imposing of its kind in this part of Poland.

Bobowa can be described as another meaningful center of Hassidism and is well-known among orthodox Jews. This tiny village is mainly associated with the manufacture of block lace. The Jews from Bobowa relocated their seat to New York and are considered to be the largest and most active Hassidism group in the world. Rabbi Asche Scharf’s funds allowed to open a restored synagogue in Bobowa, in 2003. It houses an exhibition room containing judaicas and a museum with lace work. Especially noteworthy is the frame of 1778 Aron Hakodesh, which is believed to be the most precious one in Poland. Staying in Bobowa, it is worth visiting the cemetery where the leaders of local Jews are buried.

Apart from Bobowa, Żabno once played an important role in Hassidism movement. The most famous Żabno’s leader was Shalom Dawid Unger, son of Dawid Unger from Dąbrowa Tarnowska, the author of religious works. The cemetery restored in 1992 with well preserved tombstones is the only mark of the presence of Jews in this town.

In Bochnia tourists can visit S.Fisher’s museum displaying judaicas. Moreover, a synagogue that has once been adapted to banking is worth seeing together with well preserved cemetery.

Nearby Brzesko is known as the birthplace of Mordechai Dawid Brandtstaetter, grandfather of a famous Polish writer Roman Brandtstaetter. Among the few preserved relics of the past especially worth mentioning are former synagogue and a bath-house, nowadays serving for cultural purposes. A well-kept cemetery embracing several hundred matsevahs, ohels and gravestones can also be visited.

Graveyards and places symbolizing the martyrdom of Jews are the most numerous traces of the presence of this nation in the region. Jewish cemeteries can be found in many places, sometimes they are neglected and forgotten (Szczucin, Dębica) and sometimes are untypical (for instance the military cemetery in Zakliczyn).

In the places of the mass slaughter of Jews committed by the Nazis during WWII there are symbolic monuments. In the Buczyna wood in Zbylitowska Góra we can see the monument commemorating the murder of approximately 6 000 Tarnów Jews. The mass graves hide ca. 10 000 victims including 800 children and 2000 Poles.

Tarnow is a microcosm for Poland as a whole. Shavei emissary to Krakow Rabbi Avi Baumol revisits his Polish roots